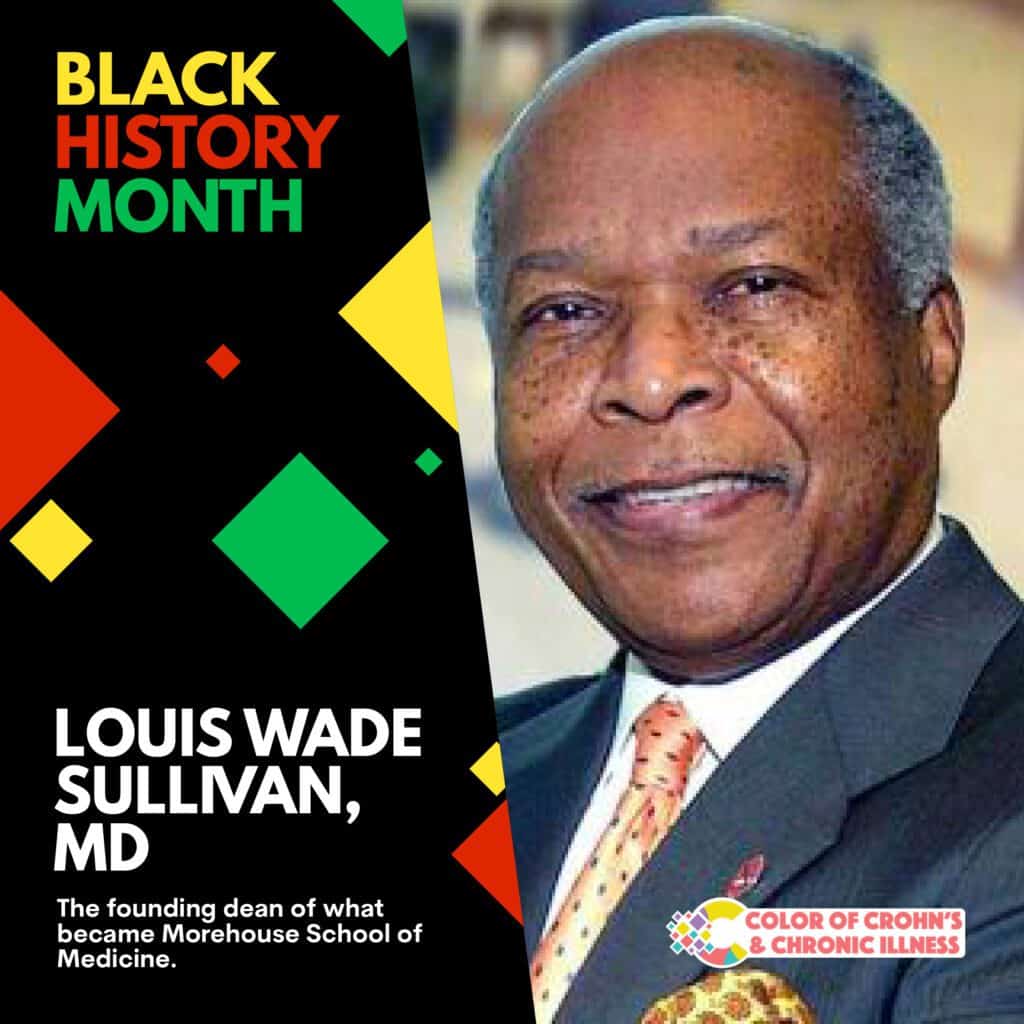

Louis Wade Sullivan, MD, grew up in the racially segregated rural South in the 1930s. There, he was inspired by his doctor, Joseph Griffin. “He was the only black physician in a radius of 100 miles,” Sullivan said. “I saw that Dr. Griffin was really doing something important and he was highly respected in the community.”

Over the decades, Sullivan became an equally profound source of inspiration. The only black student in his class at Boston University School of Medicine, he would later serve on the faculty from 1966 to 1975. In 1975, he became the founding dean of what became the Morehouse School of Medicine — the first predominantly black medical school opened in the United States in the 20th century. Later, Sullivan was tapped to serve as secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, where he directed the creation of the Office of Minority Programs in the National Institutes of Health’s Office of the Director.

Sullivan has chaired numerous influential groups and institutions, from the President’s Advisory Council on Historically Black Colleges and Universities to the National Health Museum. He is CEO and chair of the Sullivan Alliance, an organization he created in 2005 to increase racial and ethnic minority representation in health care.